Content

• The Information Timeline

• Popular, Scholarly, & Trade Publications

• Primary, Secondary, & Tertiary Materials

• Information Formats

The Information Timeline

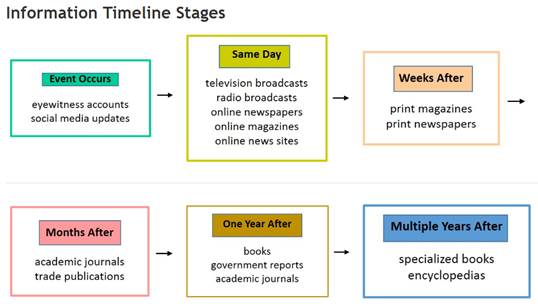

When an event or something noteworthy happens, the information about that occurrence goes through a progression of stages where it transforms into different types of information. This is the information timeline, or information cycle. As facts are revealed and discussed, the story about that event becomes richer and often more clear. Information usually starts out on informal channels or through mass media. As time progresses, popular sources of information cover the event. Months and years later, scholarly sources of information may address the event as well.

While this is the general timeline from event to recorded knowledge, not all events will merit scholarly research. In addition, at any time, information can return to the beginning stages of the timeline if related events happen to bring it to public attention.

Real-World Example

The following example follows an actual event as it progresses through the stages of the information timeline. The event is the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, commonly referred to as the BP oil disaster, in the Gulf of Mexico.

Event Occurs

At approximately 9:45 pm on April 20, 2010 an explosion and fire are reported on the BP Deepwater Horizon oil facility located in the Gulf of Mexico. At this exact moment, the only witnesses with potential information are those unfortunate enough to be in the vicinity.

Same Day

That same evening, reports begin to appear online and on television and radio programs like New York Times online, CNN, and NPR. The only information available at this time is from a few eyewitnesses, local responders, and company representatives.

Weeks

Within weeks, popular print and online magazines like Time and Newsweek have compiled reports that are slightly more complete for a general audience. There are few technical details, and while some verification has taken place, it is still too early to have a complete picture of the spill or its eventual magnitude.

Months

After a few months have passed, more information has been gathered and scrutinized. Trade magazines and academic journals have begun publishing analysis of the event from credible authors. Systematic studies and reviews appear in publications like the Journal of Coastal Research. Many of these will spawn new areas to research in the future.

One Year

After a year, full-length books and government reports are available through print and electronic sources. The books and reports contain in-depth coverage about the event and are for popular or scholarly reading. For example, the book A Hole at the Bottom of the Sea was published within a year of the spill.

Multiple Years

As years pass, the oil spill and its aftereffects are included in reference and scholarly books. General and specialized encyclopedias include an overview and basic information about the event. An example would be the entry about the spill that appears in the Gale Encyclopedia of Environmental Health.

Popular, Scholarly, & Trade Publications

Categorizing Information

It is nearly impossible not to categorize information. Categorized information allows us to make quick assumptions about the information’s intended audience, authorship, content, language, and purpose. These judgments help us to choose the correct information type to meet our academic, professional, and personal information needs. Publication, material, and format type are three ways to categorize information. Over the next three lessons, we will discuss these three types and how to identify them and their benefits and drawbacks.

Publication Type

Publication types include popular, scholarly, and trade sources. Professors will often assign a minimum or maximum number of sources from each publication type. For example, a professor may require you to retrieve at least five sources from scholarly publications like academic journals or not allow the use of any popular publications. The sections below will help you distinguish a publication as popular, scholarly, or trade.

Popular Sources

|

Popular information informs and entertains the reader. Magazines like Macleans, and Time, newspapers like the Globe and Mail, and books like an unofficial Michael Jackson biography are examples of popular publications. A popular publication will contain language easily understood by a general audience. They are usually written by journalists or freelance writers and do not undergo a formal review by experts before release. Popular publications generally do not have full citations for information used to write the piece. |

Sometimes popular information is desirable for research. Magazines and newspapers include non-technical language and are usually jargon-free for easier reading. They tend to cover issues with relatively brief, broad overviews. Popular publications can be a good place to learn the basic components of a topic, to understand the varying viewpoints surrounding an issue, or to discover potential angles to explore with deeper research. Often, popular publications report on existing research or provide context to news stories that reflect the general interest perspectives of an issue. Newspapers particularly are useful for research on local issues that may not receive much, if any, coverage outside of the region. Popular sources are great for current information because their publication cycle is more frequent than scholarly sources.

Benefits → current events, popular opinions, local issues, broad overview of a topic

Drawbacks → not evaluated by experts, topical coverage of an issue

Scholarly Works

|

Scholarly information is often required for university-level research assignments. Professors favor the use of scholarly publications, found in academic journals or books, because they are a highly credible source of information to cite. These publications typically consist of original research and studies. Scholarly publications also contain expert analysis on topics or issues; for example, a work of literature or a problem facing society. Many of them are peer-reviewed before publication. Peer-reviewed means the work undergoes a series of reviews by other experts in the field to ensure quality, credibility, and accuracy of the information. |

Experts in a field write scholarly information for other experts or academics to read and advance the knowledge of the field. The information can sometimes be difficult to understand for non-experts. Scholarly publications often use technical and scientific terminology and assume prior knowledge of the subject matter. In addition, they tend to be longer and more in-depth than popular or trade information and focus on specific aspects of an issue rather than a broad overview. Virtually all scholarly publications include a bibliography, works cited, or reference list of sources consulted or cited by the authors.

Benefits → good for academic topics that require expert study, critique, and analysis

Drawbacks → long, technical/scientific language, narrowly focused

Trade Publications

|

A trade publication falls outside of both scholarly and popular information, though it may contain elements of both. Trade publications share information between people within a specific industry in order to improve their business or field and to keep up-to-date on market trends. |

Trade publications can be very useful to research within a specific field. Professionals or reporters in the industry write information aimed at others working in the same field. The information shared in a trade publication tends to be current and to include discussion of trends and products that affect the direction of the field. Since these publications are so specialized, they are likely to address a variety of issues, viewpoints, and perspectives related to the subject matter. Most common trade publications have good reputations with experts in the industry and provide verifiable, trustworthy information. Some trade publications undergo a peer-review process like scholarly information to ensure accuracy and relevancy before publication.

Benefits → career/industry research, some are peer-reviewed, specialized

Drawbacks → some are not peer-reviewed, overly specialized

Primary, Secondary, & Tertiary Materials

Material Type

Material type is another categorization of information. A source is either a primary, secondary, or tertiary material type depending on when it was created and its purpose and scope.

It is important to understand the value in using primary, secondary and tertiary sources of information for research. Each serves a different purpose in the research process. It is not always clear how to determine the material type of a source because it can vary by academic discipline or use. This lesson will help you recognize the differences between the three material types and offer examples of each.

Primary Materials

|

Primary sources have not been critiqued, analyzed, or altered. Many primary source documents and creative works are from the time of the event. However, other primary sources, like memoirs or interviews, can exist as primary materials after the event has occurred. Examples of primary source materials vary by discipline. In the physical and social sciences, primary sources include original research studies and data sets, like census information, in their raw, unanalyzed state. In the arts, original artwork, music, movies, and literature constitute primary sources. Historic speeches, personal letters, maps, and government documents are primary materials as well. |

|

Secondary materials provide commentary, analysis, and discussion of a primary event, idea, or work. Written by experts, they address the subject from a historical or critical perspective.

Secondary materials may also exist as both a primary and secondary source so it can be difficult to discern the differences. For example, a newspaper article reporting on a current event would be a primary material, though an article from the same newspaper commenting on the same current event is a secondary.

|

Every academic discipline has secondary sources. Examples include a history book, literature criticism, subject encyclopedias, and articles that review existing research.

Tertiary Materials

|

Tertiary materials compile, index, or organize information from primary and secondary sources, often to provide an overview of a topic. This type of material rarely contains original material. Tertiary materials are usually a good source of data and facts presented with context to help you interpret a topic. They provide a broad perspective without any critique or points of view related to the topic. They may also act as a directory to other important primary or secondary sources identified in bibliography, works cited, or reference list.

|

Groups of authors - sometimes not identified by name – often write the content of many tertiary materials. Editors then review and organize the material before publication.

Examples of tertiary materials include abstracts, textbooks, almanacs, bibliographies, encyclopedias, dictionaries, directories or handbooks. Wikipedia is an example of a tertiary web source.

Information Format

Format Type

Organization, intended audience, length, and publication standards define the format type of information. Each format presents information in a different way and with a different purpose. A well-rounded research project will consult multiple format types.

Books

|

Books exist in print, electronic, and audio formats. Some electronic books have interactive properties making them a form of multimedia. Books are typically organized the same way: front cover, title page, copyright page, table of contents, chapters, index, and then a back cover. In academic libraries, many physical and electronic books are scholarly in nature, intended for research, and undergo the peer-review process before publication.

|

Other books are a source of popular information meant to entertain or inform rather than provide a citable source. Length of books can vary from ten pages to multi-volume sets of thousands of pages.

Retailers and libraries are the main source of printed books. Our Omni academic search tool allows you to search the contents of Brock University Library for available titles. You can access electronic books (ebooks) through retailers, libraries, and websites. Project Gutenberg provides books in the public domain that can be downloaded for free to any device. Google Books also has a collection of ebooks, however most are only partially available through “snippets” or “previews.” Brock University Library has a variety of ebook options including online (ebooks) that are accessed through a database like Gale Virtual Reference Library.

Academic Journals

|

Academic journals often have both print and electronic versions. Print journals will have a cover, table of contents, articles, and limited to no advertisements. Academic journals consist of separate articles that can be lengthy in comparison to magazines and newspaper articles. Most articles begin with an abstract, or summary of the work, and conclude with a bibliography, works cited, or reference list of sources consulted or cited.

|

You may also find appendices in the articles that have additional or non-essential information like maps, data tables, graphs, or images.

Most print and electronic academic journals are available through paid subscriptions only. Many publishers will sell specific issues or articles as well. Google Scholar and the Directory of Open Access Journals are sources of freely accessible journal articles, although coverage and currency of articles vary. The most comprehensive place to find academic journal articles is through library databases where you can search and access millions of full-text articles. Academic Search Complete is a library database you can use to search through nearly eight-thousand academic journals on a variety of subjects from one location.

Magazines

|

Academic journals often have both print and electronic versions. Print journals will have a cover, table of contents, articles, and limited to no advertisements. Academic journals consist of separate articles that can be lengthy in comparison to magazines and newspaper articles. Most articles begin with an abstract, or summary of the work, and conclude with a bibliography, works cited, or reference list of sources consulted or cited.

|

Some magazines fall under the category of trade publications because they provide practical information to individuals working in a particular field or industry.

Magazines are available in both print and electronic versions. Print magazines will have a cover, table of contents, articles, and advertisements. Many magazines maintain websites with freely available articles enriched with multimedia content like videos. The articles may be reproductions of print editions or new stories only found online. There are even magazines that exist entirely online with no print version. Some magazines, however, protect content behind a “paywall” where only paid subscribers can view their content. A library database like Canadian Business & Current Affairs allows students to by-pass paywalls and view full-text magazines articles.

Newspapers

|

Similar to magazines, newspapers provide information for a wide audience, cover current topics, and are a good source of popular information. In newspapers you will find articles that cover factual events and other articles that are opinion-based like letters to the editor, editorials, and op-eds (“opposite the editorial page”) columns. Newspaper articles tend to be much shorter than magazines articles and will often contain information about primary source events: who, what, when, where, and why.

|

Newspapers are usually available in print and electronic versions, on a daily or weekly basis – sometimes with multiple editions per day. Organized into sections denoted by a number and letter, print and electronic newspaper pages usually begin with headline news (section A1). The individual sections, like sports, arts, or events, will vary depending on the audience and amount of content of the newspaper. Many newspapers have online versions, or websites, where they post regularly updated content. Archival content of newspapers is typically not fully accessible online and may require payment to read the entire content. Library databases, like Canadian Major Dailies, have full-text access of current and archived newspaper content for most major Canadian newspapers.

Video and Audio

|

Many video and audio recordings provide good information for use in a research project. Depending on the content, video and audio could contain popular, scholarly, or trade information. For example, an educational video about the Civil War with photos and interviews with historians is a scholarly source. In contrast, a drama about a family in Civil War times is a popular source of information because its main purpose is to entertain. Video and audio are also sources of primary and secondary information.

|

Primary sources of video and audio are interviews, music recordings, recordings of historic events, and live-action film. Secondary sources of video and audio are documentaries and educational films or radio programs. Video and audio materials include CDs, DVDs, film and television programs, streaming media on the Web, or digital files. You can also find videos through library databases like Kanopy.

Government Documents

Government documents are information generated by provincial, local, and national levels of the government. They include a wide range of current and historical information like laws, annual reports, policies, research reports, and statistics. Government documents are authoritative, credible sources of information to use in research. In addition, government documents are generally primary sources of information.

Many government documents are available online through government agency websites such as the Government of Ontario or Statistics Canada. Consult the Brock University Library's Government & Legal Information Research Guide for key resources.

Grey Literature

Grey (or “gray”) literature is informally published material written by experts or researchers in a field. It is non-commercial information produced by organizations, advocacy groups, research labs, government agencies, and independent scholars. Examples of grey literature include conference proceedings, technical reports, clinical trials, data sets, graduate school dissertations, professors’ lecture notes, department newsletters, or blog postings from credentialed experts.

The goal of grey literature is usually to inform or influence an opinion on a topic. Most grey literature is from the medical and scientific communities, however it can be found in other subject areas. The term “grey” refers to the undefined, or uncategorized, nature of the information. Grey literature does not fall under the categories of popular, scholarly, or trade sources. Some grey literature, like clinical trials and data sets, are primary sources of information. Most other grey literature, however, is a secondary source of information. Even if you do not include grey literature as references in your project, they can be valuable as alternative perspectives or updates to ongoing research in the field.

Websites

Websites are the leading form of electronic information available, and many websites incorporate some form of multimedia presentation. Virtually any information retrieved in a Google search comes from a website. While most publication, material, and format types are accessible online, the quality, coverage, and purpose of these sources will vary significantly. There is a lot of great information online but because of the wide range of sources, it is increasingly important to scrutinize the information you find on websites.